A sample page from the online Forensic Encyclopedia:

Blood to Breath Ratio (Partition Ratio)

(also: Partition Ratio) The Blood to Breath Ratio (BBR) is the ratio of the Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) in comparison to the Breath Alcohol Concentration (BrAC). The Blood to Breath Ratio describes the difference between ethanol dissolved in the blood to ethanol exhaled in the breath at a given point in time This may be expressed as BAC:BrAC. Currently, the value of 2100:1 is adopted in North America. 2300:1 is used in the United Kingdom.

Ethanol dissolved in blood versus ethanol escaping in breath:

The BBR is based on the idea of gas permeability. Gas molecules are able to diffuse their way across the barrier between the air spaces of the lungs, the alveolar sacs, and the micro-capillaries of the blood vessels found in the lungs. The barrier is referred to as a partition, hence the often-used term Partition Ratio. The theory of this is covered in the entry on Henry's Law.

|

Ethanol molecules will build up a concentration in the blood, and that concentration will in turn exert a "pressure" on the blood vessel walls found in the lungs called the alveolar sacs, where gas exchange takes place. When enough pressure is exerted, ethanol molecules will start to migrate, or pass across, the blood vessel walls into the alveolar sacs, and now be found in the air spaces. Carbon dioxide also passes across the membrane, and oxygen goes from the air spaces into the blood, as a normal, and very necessary component of respiration.

The problem is that the partial pressure of ethanol required for this migration to occur differs from individual to individual. Your pressure is perhaps different than mine. Therefore, our BBRs could be different than the legislatively accepted value. |

So, theoretically, there are 2100 molecules of ethanol in the blood before the partial pressure of ethanol is sufficient to allow ONE molecule to migrate across the gas-permeable membrane. That gives the BBR of 2100:1. What would happen if my true pressure, and therefore my true BBR is 4200:1? (This is an outside possibility, but one that has been measured in very rare individuals). I would require 4200 molecules to be present before one could migrate across the membrane.... BUT - the breath alcohol device is calibrated to believe there are only 2100 molecules on the other side, in the blood. I had 4200... the unit would "multiply" by 2100, not my true value of 4200. My reported BrAC would be exactly HALF of my true BAC.

The exact opposite is true if an individual's measured BBR would be, hypothetically, 1050:1. (Again, this is an outlier, but BBRs this low have been reported in the scientific literature.) The breath alcohol device is calibrated to believe 2100 molecules are present in the blood for every ONE that migrates into the air space for this individual. The unit "multiplies" by 2100 instead of 1050. That individual would have a reported BrAC exactly DOUBLE their true BAC. Now we see the problem. If the BBR is different for each person, how can the breath alcohol devices be properly calibrated?

The exact opposite is true if an individual's measured BBR would be, hypothetically, 1050:1. (Again, this is an outlier, but BBRs this low have been reported in the scientific literature.) The breath alcohol device is calibrated to believe 2100 molecules are present in the blood for every ONE that migrates into the air space for this individual. The unit "multiplies" by 2100 instead of 1050. That individual would have a reported BrAC exactly DOUBLE their true BAC. Now we see the problem. If the BBR is different for each person, how can the breath alcohol devices be properly calibrated?

Determining a Blood to Breath Ratio:

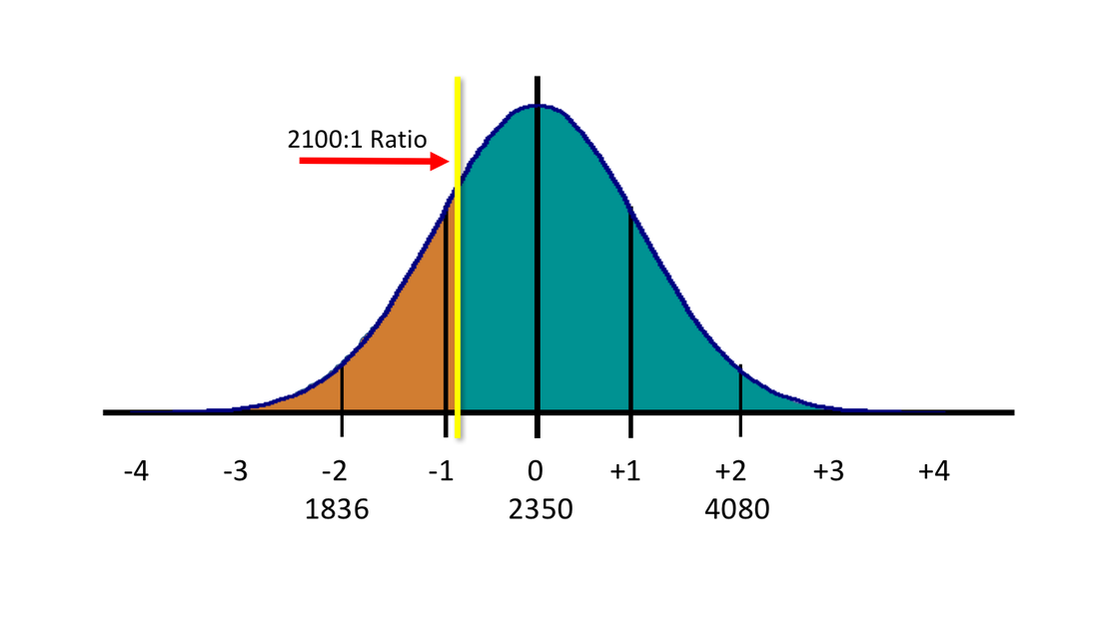

Scientific evidence suggests that a range for the value between 1850-3000:1 as being the most appropriate ratio of arterial blood to expired deep lung breath for forensic applications. A range is suggested because BBRs vary from individual to individual, with 2350:1 being the peak of the bell curve (the median, or middle value, for persons tested). Using a new ratio of 1600:1 would provide a BBR that would be representative of 99.7% of the population (or 3 standard deviations from the median). Using 2100:1 as the BBR may over-estimate the BAC in 20-25% of the population, as shown shaded in brown on the left side of the distributive curve in the diagram below.

So, any person whose actual measured BBR is higher than 2100:1 (as shown in teal green to the right of the yellow line in the diagram above) will have a reported Breath Alcohol Concentration (BrAC) lower than their true Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) value. Conversely, any individual with a BBR lower than 2100:1 (as shown in brown to the left of the yellow line in the diagram) will have their reported BrAC higher than their true BAC value.

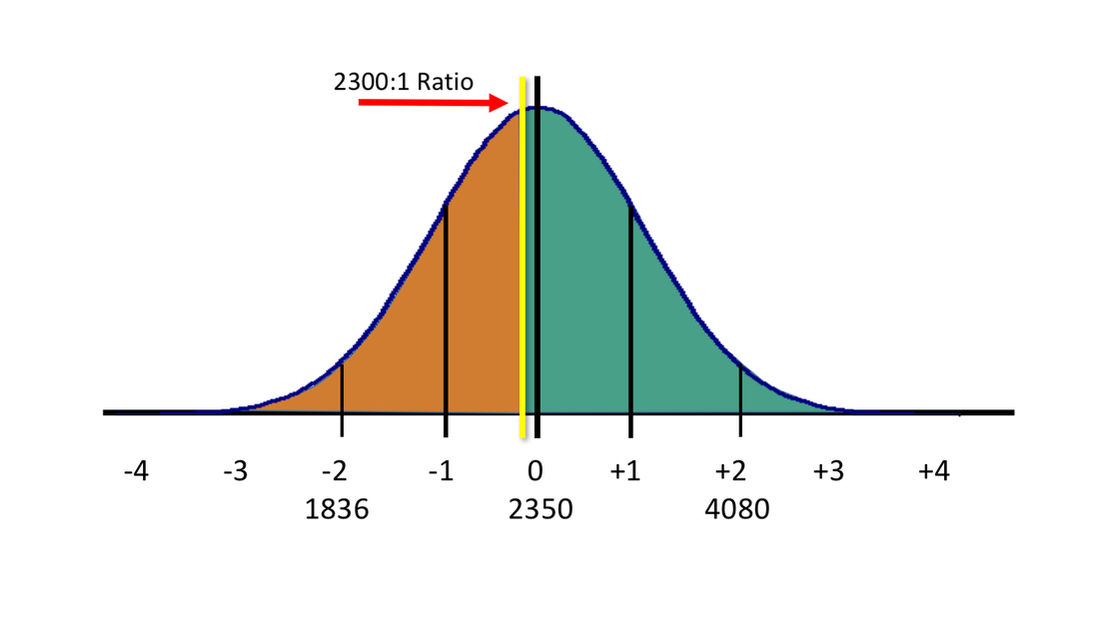

The issue is one of determining the median value of the measured BBR in humans, and then determining the acceptable outliers. The situation could be considered even more precarious for persons residing in jurisdictions where the accepted or legislated BBR is 2300:1, as is the case in the United Kingdom and many parts of Europe:

The issue is one of determining the median value of the measured BBR in humans, and then determining the acceptable outliers. The situation could be considered even more precarious for persons residing in jurisdictions where the accepted or legislated BBR is 2300:1, as is the case in the United Kingdom and many parts of Europe:

While adopting the median value may be considered scientifically acceptable, I would argue that it is not legally appropriate, due to the possibility of over-reporting or falsely inflating true BAC results in reported breath alcohol readings. It all depends upon how many people you feel it is acceptable to receive falsely-inflated readings. In laboratory experiments, these individuals may be a rarity. In reality, the number of individuals in this situation is unknown.

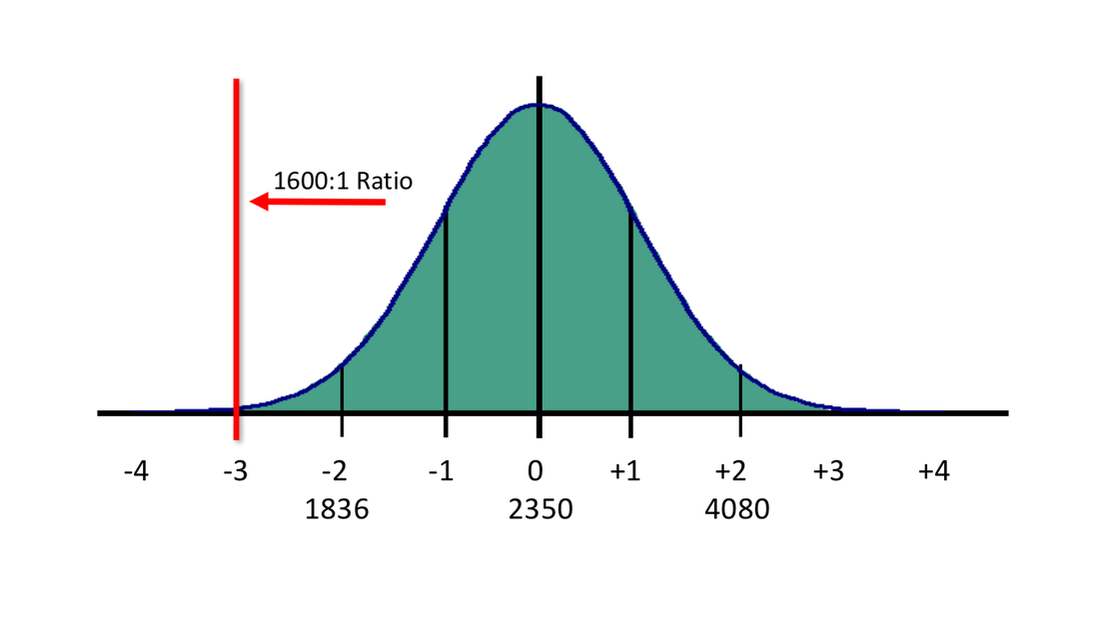

From a pragmatic point of view, perhaps it would be preferable to re-calibrate the devices to use something along the lines of a 1600:1 ratio, thereby under-reporting ALL BrAC readings. Those individuals whose true BBR was close to 1600:1 would have a truer reported value, while those whose real BBR was 2350:1 and beyond would have a lower reported reading, perhaps drastically so. This would accomplish the goal, perhaps idealistically, of eliminating or reducing the incidences of persons falsely accused due to BBR calibration issues.

From a pragmatic point of view, perhaps it would be preferable to re-calibrate the devices to use something along the lines of a 1600:1 ratio, thereby under-reporting ALL BrAC readings. Those individuals whose true BBR was close to 1600:1 would have a truer reported value, while those whose real BBR was 2350:1 and beyond would have a lower reported reading, perhaps drastically so. This would accomplish the goal, perhaps idealistically, of eliminating or reducing the incidences of persons falsely accused due to BBR calibration issues.

Figure 3 - Moving the legislatively accepted BBR to 1600:1 will lower the reported BrAC readings overall, but would lessen the impact of falsely elevated BrAC readings. The new BBR would provide readings of about 75% of current values (As an example, a 0.100 BrAC would now be reported as 0.076 using a lower ratio)

|

|

References:

- Gainsford, A. R. et al, A Large-Scale Study of the Relationship Between Blood and Breath Alcohol Concentrations in New Zealand Drivers, Journal of Forensic Sciences, Vol. 51, No. 1, Pages 173-178, (January 2006).

- Gullberg, R. G., Common Legal Challenges and Responses in Forensic Breath Alcohol Determination, 2004, Indiana University Center for Studies of Law in Action, “Borkenstein Course”.

- Gullberg, R. G., Breath Alcohol Measurement Variability Associated with Different Instrumentation and Protocols, Forensic Science International 131 (2003) 30-35.

- Jones, A.W., “Determination of Liquid/Air Partition Coefficients for Dilute Solutions of Ethanol in Water, Whole Blood, and Plasma”, 7: 193-197, 1983. Journal of Analytical Toxicology.

- Jones, A. W., Concerning Accuracy and Precision of Breath-Alcohol Measurements, Clinical Chemistry, 33/10, 1701-1706 (1987)

- Jones, A. W., Andersson, L., Comparison of Ethanol Concentrations in Venous Blood and End-Expired Breath During a Controlled Drinking Study, Forensic Science International 132, Pages 18-25, (2003).

- Jones, A. W., Andersson, L., Variability of the Blood/Breath Alcohol Ratio in Drinking Drivers, Journal of Forensic Science 41(6), pages 916-921, (1996).

- Jones, A. W.. Beylich, K. M., Bjorneboe,A, Ingum, J., and MorIand, J., “Measuring Ethanol in Blood and Breath for Legal Purposes: Variability between Laboratories and between Breath-Test Instruments” Clinical Chemistry, Volume 38, Number 5, pages 743-747, 1992.

- Labianca, D. A., The Flawed Nature of the Calibration Factor in Breath-Alcohol Analysis, Journal of Chemical Education, Vol. 79, No. 10, October 2002.

- Simpson, G., Accuracy and Precision of Breath Alcohol Measurements for Subjects in the Absorptive State, Clinical Chemistry, 33/6, 753-756 (1987).